The qPCR analysis of vaginal microflora for the diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis

1«Lytech» Ltd, 3A/2 Malaya Semyonovskaya str., Moscow, 107023 Russia; *e-mail:

senina_maria@mail.ru

2«Lytech Laboratory» Ltd, 3A/2 Malaya Semyonovskaya str., Moscow, 107023 Russia

Keywords: real-time PCR; Eggerthella; Bacterial Vaginosis–Associated Bacteria ;Megasphaera type 1; Femoscreen

DOI: 10.18097/BMCRM00084

The correct information about of the vaginal microflora plays an important role in preventing the occurrence of urinary tract infections and sexually transmitted infections among women. Disbalance of obligate and facultative microflora causes disbacteriosis, a risk factor for emergence of infectious diseases. It is known that the cause of bacterial vaginosis (BV) is not a single pathogen but a impairments in of the general balance of the vaginal microflora, which manifests a decrease of the normal microflora (Lactobacillus spp) and intense increase of pathogenic aerobic and anaerobic bacteria. The development of molecular genetic analysis methods, in particular, approaches based on the use of polymerase chain reaction (PCR), significantly expanded understanding of the diversity of microbial biotopes, including identification of the key and new «players» in the development of BV. The aim of our study was3 to evaluate the performance of real-time PCR kit «Femoscreen» («Lytech», Russia) for comprehensive BV diagnosis.

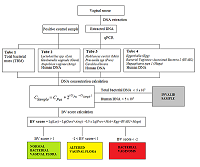

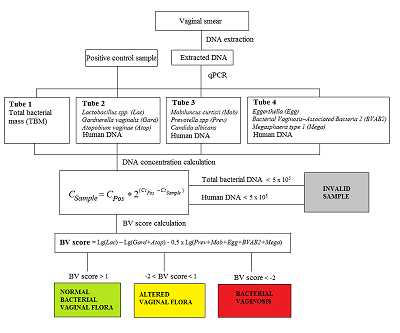

Registration of amplification products come off an amplification reaction is made at each amplification cycle in real time. A number of an amplification cycle where the fluorescence curve intersected a border line (Ct) is automatically calculated by analyzing program using specific tuning values. The value of the Ct is negatively related to a concentration of DNA in a sample. For quantitative evaluation, Ct value (a number of an amplification cycle where the fluorescence curve intersected a border line) of sample being examined is compared to a Ct value of a PCS (Positive Control Sample) with a known DNA concentration (Fig. 2). DNA concentration in an analyzed sample is calculated according to the formula:

| $${{\rm C}}_{{\rm Sample}}{\rm =\ }{{\rm C}}_{{\rm PCS}}\times {\rm \ }{{\rm 2}}^{{\rm (}{{\rm Ct}}_{{\rm PCS}}{\rm -}{{\rm Ct}}_{{\rm Sample}}{\rm )}}$$ |

(1),

|

|

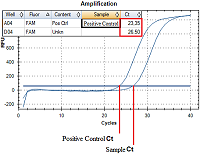

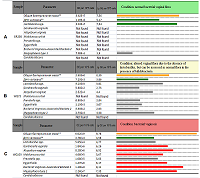

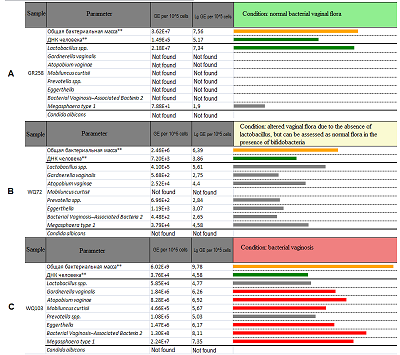

Figure 3.

Examples of the interpretation for the samples referred to the group «normal bacterial vaginal flora» (A), «altered vaginal flora» (B) and «bacterial vaginosis»(C).

|

|

CLOSE

|

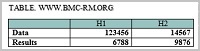

Table 1.

The Nugent scoring system (from 0 to 10) for diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis by microscopy.

|

|

CLOSE

|

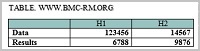

Table 2.

The obtained values of diagnostic sensitivity and specificity of the «Femoscreen» reagent kit.

|

REFERENCES

- Martin, D.H., Zozaya, M., Lillis, R., Miller, J., Ferris. The microbiota of the human genitourinary tract: trying to see the forest through the trees. MJ.Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 2012; 123:242-56.

- Morris, M., Nicoll, A., Simms, I., Wilson, J., Catchpole, M. Bacterial vaginosis:a public health review. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 2001;108: 439–450. DOI

- Hillier, S.L., Nugent, R.P., Eschenbach, D.A., Krohn, M.A., Gibbs, R.S., et al. Association between bacterial vaginosis and preterm delivery of a low-birth-weight infant. The Vaginal Infections and Prematurity Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1995; 333: 1737–1742. DOI

- Silver, H.M., Sperling, R.S., St Clair, P.J., Gibbs, R.S. Evidence relating bacterial vaginosis to intraamniotic infection. Am J Obstet Gynecol. N Engl J Med. 1989; 161: 808–812. DOI

- Hillier, S.L., Martius, J., Krohn., M, Kiviat, N., Holmes, K.K., et al A case-control study of chorioamnionic infection and histologic chorioamnionitis in prematurity. N Engl J Med.1988; 319: 972–978. DOI

- Sweet, R.L. Role of bacterial vaginosis in pelvic inflammatory disease. Clin Infect Dis. 1995; 20: S271–S275. DOI

- Hillier, S.L., Kiviat, N.B., Hawes, S.E., Hasselquist, M.B., Hanssen, P.W., et al. Role of bacterial vaginosis-associated microorganisms in endometritis. Am J Obstet Gynecol.1996;175: 435–441. DOI

- Wiesenfeld H, Hillier S, Krohn M, Amortegui AJ, Heine RP, et al. Lower genital tract infection and endometritis: insight into subclinical pelvic inflammatory disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2002; 100: 456–463. DOI

- Haggerty, C.L., Hillier, S.L., Bass, D.C., Ness, R.B. Bacterial vaginosis and anaerobic bacteria are associated with endometritis. Clin Infect Dis. 2004; 39: 990–995. DOI

- Schwebke, J.R., Schulien, M.B., Zajackowski, M. Pilot study to evaluate the appropriate management of patients with coexistent bacterial vaginosis and cervicitis. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol.1995; 3: 119–122. DOI

- Schwebke, J.R., Weiss, H.L. Interrelationships of bacterial vaginosis and cervical inflammation. Sex Transm Dis. 2002; 29: 59–64 . DOI

- Wiesenfeld, H.C., Hillier, S.L., Krohn, M.A., Landers, D.V., Sweet, R.L. Bacterial vaginosis is a strong predictor of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2003; 36: 663–668. DOI

- Allsworth, J.E., Peipert, J.F. Severity of bacterial vaginosis and the risk of sexually transmitted infection. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011; 205: 113.e1-113.e6. DOI

- Cherpes, T.L., Meyn, L.A., Krohn, M.A., Lurie, J.G., Hillier, S.L. Association between acquisition of herpes simplex virus type 2 in women and bacterial vaginosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2003; 37: 319–325. DOI

- Myer, L., Kuhn, L., Stein, Z.A., Wright, T.C. Jr., Denny,L. Intravaginal practices, bacterial vaginosis, and women’s susceptibility to HIV infection: epidemiological evidence and biological mechanisms. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005; 5:786–794. DOI

- Eschenbach, D.A. Bacterial vaginosis and anaerobes in obstetric-gynecologic infection. Clin Infect Dis. 1993; 16: S282–S287.

- Spiegel, C.A. Bacterial vaginosis. Rev Med Microbiol. 2002;13: 43–51. DOI

- Wang, K.D., Su, JR. Quantification of Atopobium vaginae loads may be a new method for the diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis. Clin Lab. 2014;60(9):1501-8. DOI

- Shipitsyna, E.,Roos, A., Datcu, R., et al. Composition of the vaginal microbiota in women of reproductive age - sensitive and specific molecular diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis is possible? PLoS One. 2013; 8: e60670. DOI

- Verhelst, R., Verstraelen, H., Claeys, G., Verschraegen, G., Delanghe, J., et al. Cloning of 16S rRNA genes amplified from normal and disturbed vaginal microflora suggests a strong association between Atopobium vaginae, Gardnerella vaginalis and bacterial vaginosis. BMC Microbiol. 2004; 4: 16. DOI

- Fredricks, D.N., Fiedler, T.L., Marrazzo, J.M. Molecular identification of bacteria associated with bacterial vaginosis. N Engl J Med. 2005; 353:1899 1911. DOI

- Verstraelen, H., Verhelst, R., Claeys, G., Temmerman M, Vaneechoutte M. Culture-independent analysis of vaginal microflora: the unrecognized association of Atopobium vaginae with bacterial vaginosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004; 191: 1130–1132. DOI

- Zozaya-Hinchliffe, M., Martin, D.H., Ferris, M.J. Prevalence and abundance of uncultivated Megasphaera-like bacteria in the human vaginal environment. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008; 74: 1656–1659. DOI

- Zariffard, M.R., Saifuddin, M., Sha, B.E., Spear, G.T. Detection of bacterial vaginosis-related organisms by real-time PCR for Lactobacilli, Gardnerella vaginalis and Mycoplasma hominis. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2002; 34: 277–281. DOI

- Sha, B.E., Chen, H.Y., Wang, Q.J., Zariffard, M.R., Cohen, M.H., et al. Utility of Amsel criteria, Nugent score, and quantitative PCR for Gardnerella vaginalis, Mycoplasma hominis, and Lactobacillus spp for diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis in human immunodeficiency virus-infected women. J Clin Microbiol. 2005; 43: 4607–4612. DOI

- Cartwright, C.P., Lembke, B.D., Ramachandran, K., Body, B.A., Nye, M.B., et al. Development and validation of a semi-quantitative, multi-target, PCR assay for the diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2012; 50: 2321–2329. DOI